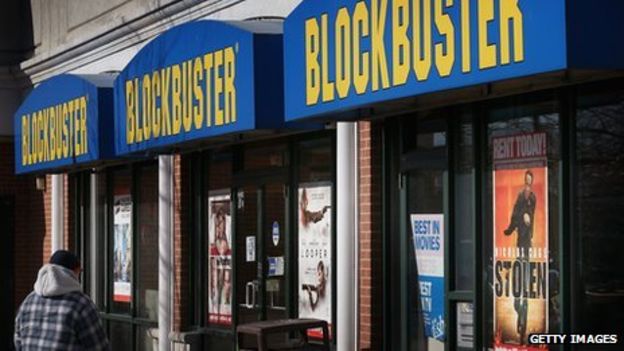

They were on the main street of every large and small town. They were in suburbs and there were multiples of them in cities. They were crowded with people most nights of the week, especially Fridays. Many were small businesses owned by families, but there were also large chains who owned stores across states and countries.

Video stores.

Slowly over the past decade they’ve almost all disappeared. The giant of the industry, Blockbuster, has one store left in Australia and one store left in the US. The US store is making the most of its notoriety or nostalgia by selling memorabilia. While there are movie vending kiosks popping up to cater to those that are still using DVDs, the die looks cast. Streaming services like Netflix and faster internet/data connections are combining to erase physical media rentals.

In other words, a once iconic storefront that existed in most nearly every town has been disrupted by improving technology. Behaviour changed around the technology, with the ability to watch on demand and binge watch whole TV seasons in one go. No need to return discs or tapes by a due date any longer and all for a monthly fee less than two overnight rentals.

No matter where you look, you can find a similar story. Nokia seemed unassailable as the world’s largest mobile phone company. Then Apple released the iPhone in 2007. Polaroid and Kodak were taken to the cleaners by the shift to digital cameras.

Sometimes it doesn’t even have to be straight disruption by one company. Consumers may do the disrupting. The latest example is Kraft-Heinz in the US. Over the past week the Kraft-Heinz share price has dropped over 30%, with the dividend being cut a similar amount.

Among a host of problems, Kraft-Heinz has been under pressure as consumers move to cheaper private label brands or alternatively choose more health-conscious options. When your best-known food products are processed packaged options that are laden with salt and carbs, changing tastes and health conscious consumers become a real problem.

Many investors didn’t see any issue because of some of Kraft-Heinz’s most notable shareholders – Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway and noted Brazilian private equity fund 3G. Showing even the best can get it wrong or just be shown up by market changes that they may not see. If Warren Buffett can’t see shifting consumer sentiments, and what they mean for the businesses he owns, what chance do the rest of us have?

The arguments for owning Kraft-Heinz? It’s defensive, it pays a good dividend, it’s a household name and Warren Buffett owns it.

Excluding the Warren Buffett reason, these are reasons why many DIY investors find themselves buying a handful of individual blue-chip stocks. A few scant observations noting previous stability of the companies they’re getting into. It’s hardly research or a robust investment philosophy and it overstates the company’s past as being some sort of indicator for its future.

In the current franking credit debate, when the discussion moves away from the loss of income, many retirees can be heard highlighting the risk they would have to take to make up the difference.

Recently in The Australian, a retired couple with an SMSF were profiled, voicing their frustration about the changes.

The wife said, “the only alternatives to relying on government handouts are restructuring their portfolio with riskier assets or reducing their standard of living.”

While the husband, when speaking of retirees in general said, “others might take extra risk and potentially “shoot themselves in the foot”.

As we noted last week, these DIY retiree portfolios are meant to sustain multi-decade retirements, but they are often extremely undiversified and overwhelmingly reliant on a handful of individual companies. Meaning the gun is already pointed at the big toe with the hammer cocked!

Do they really have to take extra risk?

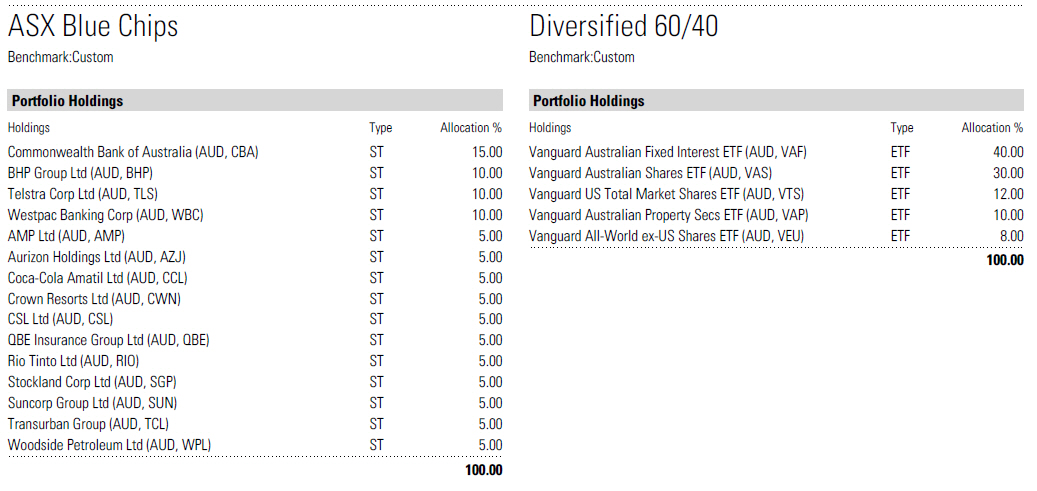

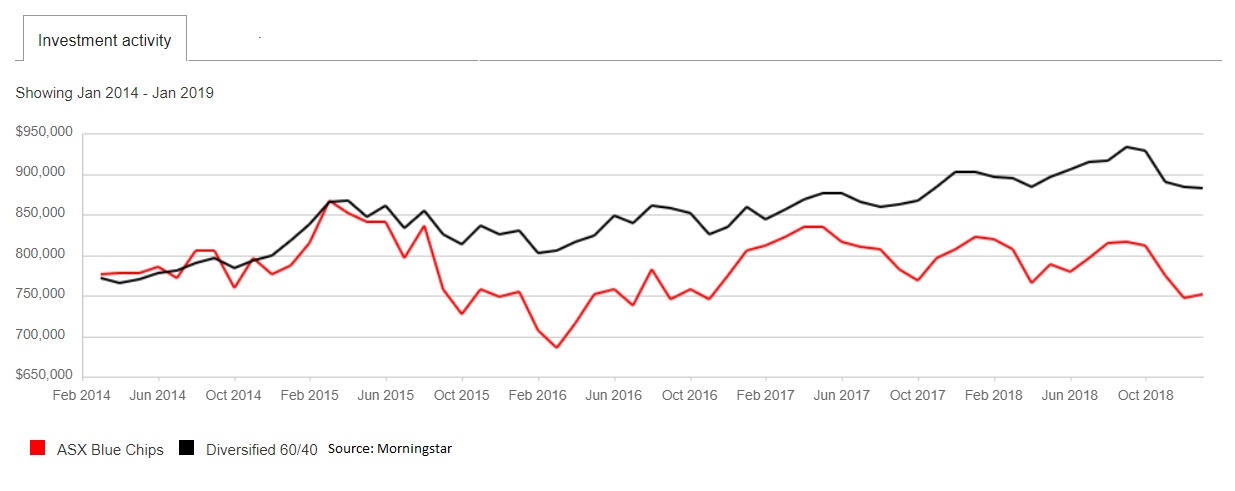

We’ve gone back five years and picked 15 blue chips, all decent dividend payers who were inside the ASX top 30 at the time and ran them against a diversified portfolio of Vanguard exchange traded funds (ETFs). The results were somewhat surprising, especially given the asset allocation of the diversified portfolio. The diversified 60/40 had 40% of its assets in fixed interest, while the blue chips were solely comprised of stocks.

The starting position was $750,000 and the portfolios were rebalanced on a yearly basis. There was no reinvestment of distributions, with the intention to take them as income. While the blue chips portfolio paid more in income over the five years, $200,342 vs $157,058, the growth was a different story. A final market value of $773,971 for the blue chips against $900,082 for the diversified portfolio.

Firstly, this is only a short time frame and the ASX blue chips represents something of a randomised portfolio (but what DIY construction isn’t?), yet it does bring into question the argument those affected by potential franking credit changes need to take more risk.

It shows the potential exists to lower portfolio risk while continuing to derive a satisfactory return and achieve the outcomes an investor is after. In this case, the lower distributions in the diversified portfolio are easily accounted for by the higher capital growth. Leaving the owner of that portfolio with the luxury of a comfortable buffer to draw capital to make up the difference.

Also note the behaviour of portfolios. The volatility of the diversified portfolio is almost half that of the ASX blue chips portfolio. The standard deviation of the blue chips is 11, while it’s 5.88 for the Diversificed 60/40. This isn’t a great surprise, given the blue chips comprises just 15 stocks, while the Diversified 60/40 comprises 6285 stocks and 561 bonds.

Both of these portfolios would have served their owners quite well over the time frame used. You might say “well I’d take the Diversified option because of the returns”. Over a longer timeframe the returns may be a different story, but even if the results had been flipped or even if they were identical, the returns aren’t really the story.

It’s the risk to achieve those returns.

A lot of retirement planning is focused on the ‘what if’ of what can go wrong and the ‘risks’ retirees face, but DIY investors and DIY retirees who buy individual stocks have a habit of looking at risk through the prism of the past. Great companies, household names, ongoing dividends.

Historical unbroken and increasing dividend streaks don’t make a case for unbroken and increasing dividend streaks into the future. A great company won’t necessarily be a great company next year. If a Kraft-Heinz falls from favour in your 6285-stock portfolio/561 bond portfolio, you’re unlikely to feel it.

In the 15-stock portfolio? Those are the people you see on the news shaking their fists at management during AGMs. A company going bad or being disrupted is a big thing when an investor is undiversified.

The best defence against portfolio disruption? Diversification.

This represents general information only. Before making any financial or investment decisions, we recommend you consult a financial planner to take into account your personal investment objectives, financial situation and individual needs.