You might remember it. Though it seems so long ago right now. There was a big kerfuffle. It was about franking credit cash refunds. In short, former Labor leader Bill Shorten was going to do away with them. In response, Australia’s self-funded retirees made it their mission to do away with Bill Shorten.

Retirees: 1. Bill Shorten: 0.

Less than a year on. There has been fire. There has been pandemic. Bill Shorten might be feeling better about losing that election. What about those retirees? Highly doubtful they want Mr Shorten back, but he did present them with an opportunity. To address the red flags in their portfolios. Those red flags were clear.

The SMSF Association conducted a survey in 2018, finding: “two-thirds of self-managed superannuation funds consider a portfolio invested in 20 shares to be well-diversified”.

Holding 20 shares is not well diversified.

SMSFs are often poorly diversified because they crowd into the blue-chip dividend payers chasing the yield they offer and those franking credit refunds. When these investors did broaden their horizon, it was merely a variant of their blue-chip favourites. Usually hybrid securities.

What are hybrids?

They’re another way companies can borrow money from investors. Somewhat like a bond or fixed interest. But they’re not. An investor lends their money to a company who in turn pays a rate of return. Much better than cash. At maturity the investment can be converted to shares, cashed in, or rolled over into a new security. Some hybrids are traded on the ASX like a share. Self-directed retirees use them, along with financial advisers who don’t have a rigorous process. Some advisers straight out categorise them as fixed interest.

The trap? There can be multiple, but the big issue, as noted, these products are too often taken up by retirees looking for income and as a replacement for cash or fixed interest. Cash rates fall and when money rolls out of term deposits those investors look for a better deal. What could be better than well-known household names, such as the banks, offering tradable securities with a high yield?

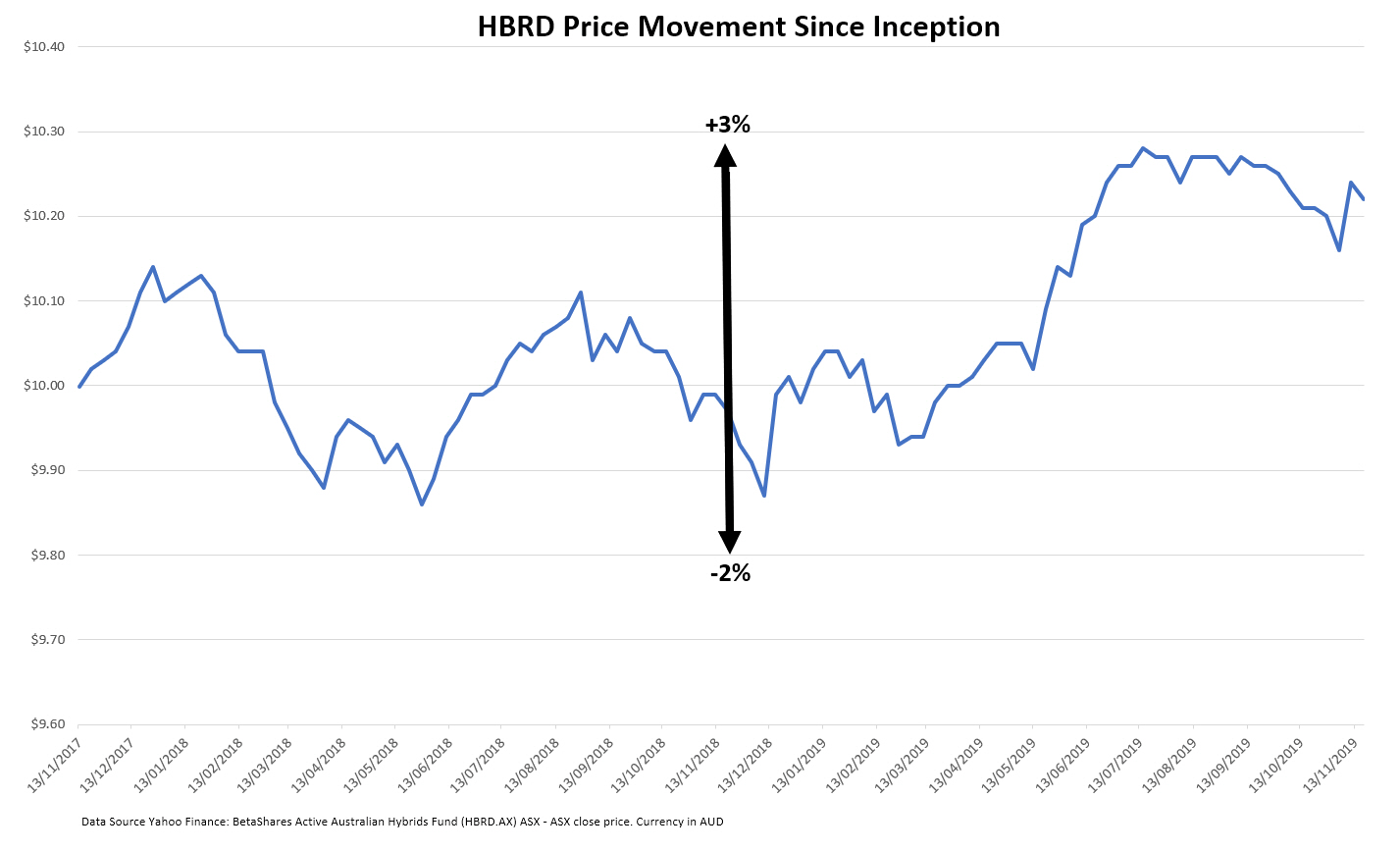

There’s even a diversified exchange traded fund of hybrids. Betashares Hybrids Fund has 45 holdings. For this example, we’ll use it as a proxy for the whole sector that has been seeing increased interest. The chart of the tradeable securities looks like this in the first two years since its inception in 2017.

The chart looks a bit rocky, but so does a rock garden from an inch away. The arrows provide the context. The movements are actually quite small. In the first two years since the fund came into existence, it’s never moved 2.8% higher or 1.4% lower, than its original $10 issue price. Seemingly low volatility. And it’s reliably paid dividends.

The exact type of capital stability a retiree would want. A reliable replacement for cash or fixed interest in these low yielding times. Until recently.

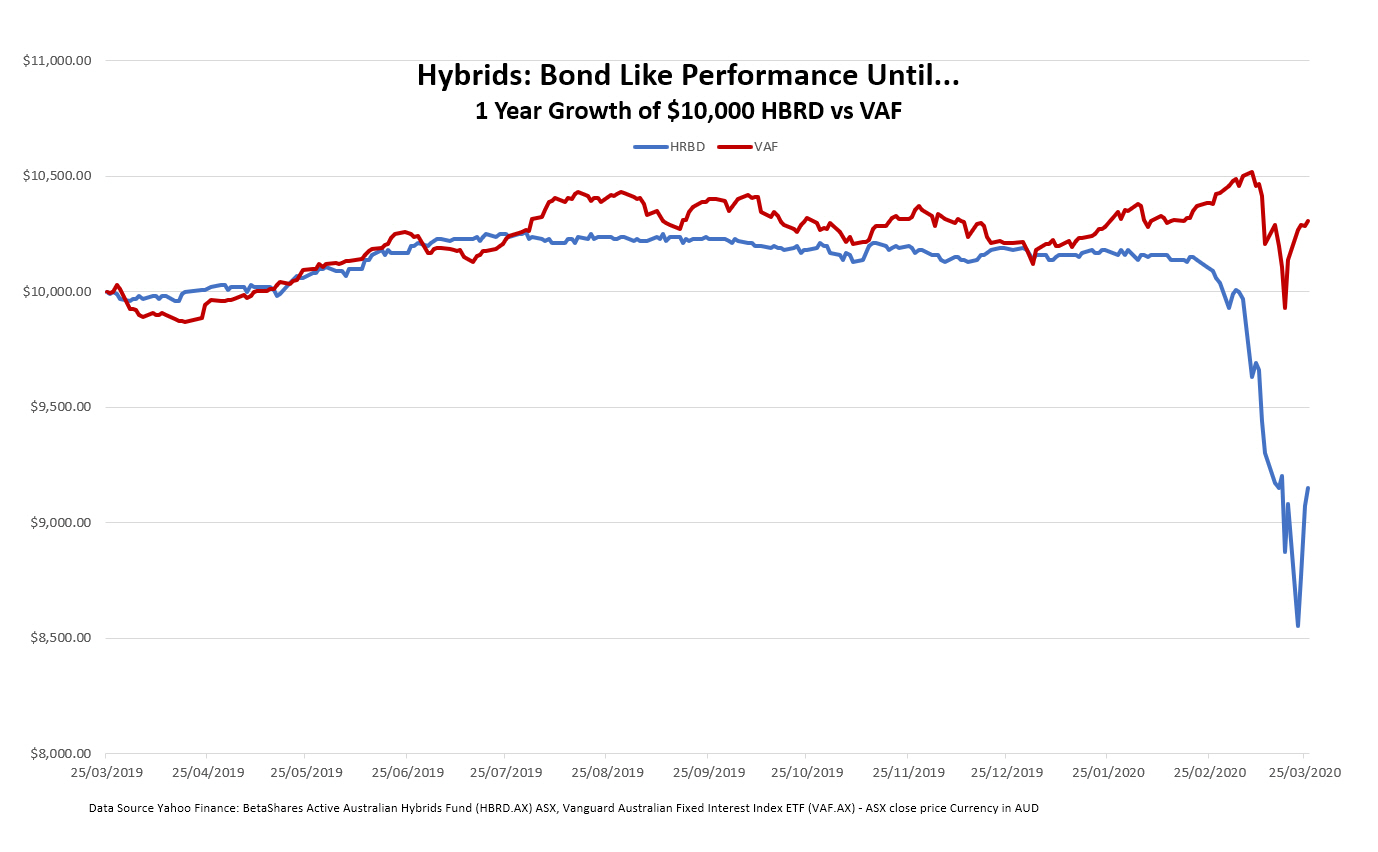

The chart above is comparison of the same fund over the last year (again the blue) against Vanguard’s Australian Fixed Interest Fund (red). Over the past 12 months Vanguard’s fund has much more price volatility. The hybrid fund seems remarkably stable. Up until the moment it really counts. Then the hybrid fund falls 15.6% in a month.

This isn’t an exercise in highlighting one investor may have lost more than another. Virtually every investor has taken some sort of hit recently. Some more than they expect. There is a good reason investors should have various asset classes in their portfolio. When push comes to shove, they will behave differently. In the event of a tumble, an investor should expect the defensive part of their portfolio to hold reasonably steady.

This is the problem with assuming hybrids can be a substitute for fixed interest or cash. In good or average times, they perform like a stable income product. As shown by the chart, they’re actually less volatile. In bad times, they suddenly behave in a similar fashion to share prices. Investors unaware of this just received a big portfolio shock.

Fixed interest and/or cash in a portfolio should act as a stabilisers or a buffer when an event occurs that sends share prices tumbling. Why is this important?

Mentally: the losses an investor is seeing on the TV or newspaper won’t be the losses they’re seeing in their portfolio. A relief in times of turmoil.

Financially 1: if an investor needs cash they will be liquidating after a drop across their whole portfolio. If shares have fallen 20% and their so called “stabiliser” has fallen 15% in unison, they’ve lost the option to manage their portfolio according to any prior rules set in place about cash management.

Financially 2: An investor loses the opportunity to take advantage of the situation. They can’t rebalance their portfolio in any meaningful way. Expected returns increase after large market falls. Switching some cash and fixed interest into shares can help increase future returns. It also keeps a portfolio in line with an investor’s risk profile.

An investment philosophy is an incredibly important document. It’s drawn up ahead of time and acts as a rule book. A guiding set of principles. It’s referred to in good times and bad. It ensures a portfolio is managed to a high standard. It spells out the investment products to be used. It highlights investment products to be excluded.

Investors, or the advisers they delegate to, need a robust investment philosophy specifically for this reason. It needs to be based on evidence. Data across all asset classes stretching back centuries. Hybrids have a short track record. On the available evidence they’re not a stable substitute for fixed interest and they don’t provide the capital appreciation of shares.

Investors require one or the other. Not the worst of both.

A product to be excluded.

This represents general information only. Before making any financial or investment decisions, we recommend you consult a financial planner to take into account your personal investment objectives, financial situation and individual needs.