It’s been a few years since the term ‘moneyball’ was widely appropriated throughout the sporting world. In case you missed it, Moneyball was a 2003 book by Michael Lewis (later a 2011 film starring Brad Pitt) following the Oakland Athletics baseball team. The team had the third lowest player payroll in US baseball, but general manager Billy Beane attempted to overcome this through using analytics and evidence based strategies to find undervalued players and compete with larger teams.

Despite losing star players, Oakland’s 2002 season was famous for besting their previous season, going on a 20 game winning streak and having the second best winning percentage in the league. A winning percentage only bettered by the New York Yankees who spent three times more on player salaries than Oakland.

How does this relate to investing? The concept of finding players who are undervalued by the market isn’t so different to tilting a portfolio to incorporate value companies that are out of favour with the market for some reason. The end goal is a better return through increasing risk, but using historically compensated risk, to achieve that better return.

There are three givens when it comes to compensated risk factors. These givens are all based on academic research.

First, the market itself. Shares are riskier than bonds so they offer higher expected returns.

Second, small companies have higher expected returns than large companies because they are more of an unknown quantity. Think an established star player vs a first year player. Superstars tend to perform according to their pay packed so there may not be much upside. For the first year player, expectations are low, so the pay is low, but they may provide a significant upside.

Finally, value companies offer higher expected returns than large and successful companies because they are out of favour with the market for some reason. In this instance you might think of a player recovering from a long term injury, maybe one with offield issues or just misused by a previous team. For value companies, they may have been poorly managed, missed guidance or have been going through a restructure meaning their shareprice has been dented, but their potential remains.

In Oakland’s case, GM Billy Beane found certain important statistics were underutilised in baseball and the players who ranked highly in those statistics were often undervalued and not well regarded in the league. This meant Beane could build a high performing, albeit unfashionable team, within Oakland’s salary constraints.

On the back of the book and the film, Billy Beane became a much more widely known figure and his and his team’s methods attracted a lot more scrutiny. Oakland hasn’t performed as well since, so some assumed it was a fad and a flash in the pan. Not the case. Essentially Oakland was pulled back to the pack because many other teams began incorporating the same statistical analysis into their team building.

So long term in baseball it becomes harder to find value and outperform the market. In contrast when investing, the outperformance from value generally appears over the longer term – if an investor maintains discipline.

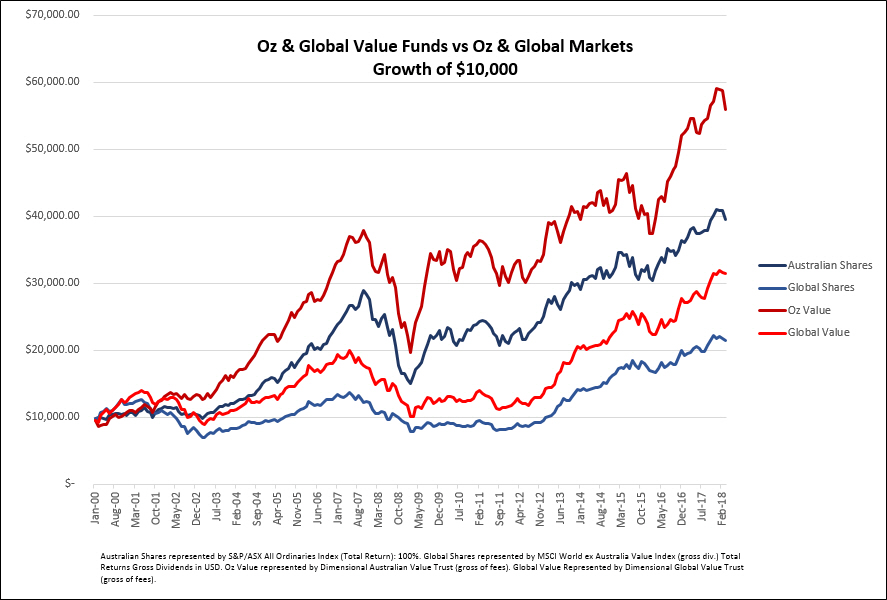

As the following chart shows with Australian and Global value returns vs their respective benchmarks since 2000. To note, the red lines represent Australian and Global value funds while the blue lines represent their respective Australian and Global market benchmarks.

Now you don’t build your whole portfolio on value funds because value premiums are not always available. Sometimes yearly returns will fall behind market returns and value funds also come with higher volatility. However, as part of a diversified portfolio a tilt to value can help increase overall return.

In baseball the increasing use of statistics and research has meant a change from scouting and recruiting players based on intuition by scouts and managers. Much as statistical analysis has contributed to less guess work when investing.

As Billy Beane notes when comparing baseball’s changes to the investment industry, “thirty years ago, stockbrokers used to buy stock strictly by feel. Let’s put it this way: Anyone in the game with a 401(k) has a choice. They can choose a fund manager who manages their retirement by gut instinct, or one who chooses by research and analysis. I know which way I’d choose.”

Wise words.

This represents general information only. Before making any financial or investment decisions, we recommend you consult a financial planner to take into account your personal investment objectives, financial situation and individual needs.