A few times a year market indices rebalance. ASX 200, 300, S&P 500, FTSE 100 etc. Happens all over the world. Companies enter and exit various indices. It’s a time when companies who might have had a roaring time of late get to move up in the world. For those who may have fallen on hard times, it’s unwanted recognition. They’re slipping down in the pecking order. No longer growing, but shrinking.

One of the more notable exits from a major index recently was that of Wirecard.

There’s a belief that capital markets are the best place to invest because of scrutiny and oversight. They are well regulated, and companies listed are tested daily with price discovery relative to the publicly available information all investors have access to.

For the most part this is true. There is still plenty of room for dubious or even fraudulent actions on markets. Generally, the worst stuff occurs down in the micro-cap space. Mates and associates vending in mining projects located in suspect jurisdictions for big pay offs to raise capital from shareholders with stars in their eyes. Prices are pumped for a payday. The same old projects can be recycled several times over. Relinquished and then reacquired the next time a boom in minerals comes along.

Occasionally, suspect companies are found beyond the micro end of the market. This is where tricky accounting starts. The BIG Un fiasco of recent times was one that got beyond the very small end of our own market due to some dubious accounting methods. You may not have heard of Wirecard because it’s listed in Germany. On the DAX 30. The most prestigious blue chip companies listed in Germany. At one point, it certainly looked like Wirecard deserved to be there. It had a peak market capitalisation of 24 billion Euro.

Only problem, Wirecard had been cooking its books.

What kind of company would do such a thing? Wirecard was a payment processor. In their early days they catered to a clientele the more reputable payment companies didn’t want to touch, due to association or regulatory issues. Specifically, pornography and gambling transactions. Over the last decade they spent a lot of time and money acquiring other obscure payment processors throughout Asia.

Throughout this time there were ongoing questions over Wirecard’s books. Allegations of sales being inflated. Accounts not lining up between various international businesses. Roundtripping transactions to inflate revenue, which can be helpful to give the impression of business growth. Investors are known to ignore businesses making money to chase growth stories. The shareprice will rip upwards.

The questions started from the short sellers. Traders who borrow stocks to sell at the current price, wait for the price to fall, then buy the stock back at the lower price and return it to the lender and pocket the difference. If a short seller thinks they’ve spotted a fraud, they think they’ve spotted a declining share price. After taking a short position, they’ll then release their research on why the believe a company is crooked.

For early Wirecard short sellers, it didn’t work out as planned. One was charged with market manipulation and jailed. Wirecard sued and attacked many others. This only increased the questions over their business. The Financial Times took a regular interest. This culminated with the German financial regulator (Bafin) investigating and referring Financial Times journalist Dan McCrum to the Munich Public Prosecutor for offences under the securities trading act.

One of the big issues was the German financial regulator. It seems they spent more time attempting to protect Wirecard and investigating its critics than investigating the allegations of fraud. They temporarily banned short selling in Wirecard, claiming the shareprice was being manipulated. The other big issue, Wirecard’s auditor EY (Ernst & Young) couldn’t spot the fraud. Wirecard filed for insolvency in June after EY finally wouldn’t sign off on their books when 1.9 billion Euro, said to be sitting in a Philippines bank, couldn’t be accounted for.

EY privately claimed responsibility for uncovering the fraud, despite the fact they’d been signing off on Wirecard’s accounts for a decade! The June announcement came about after KPMG were brought in for a special audit to investigate the claims by the Financial Times.

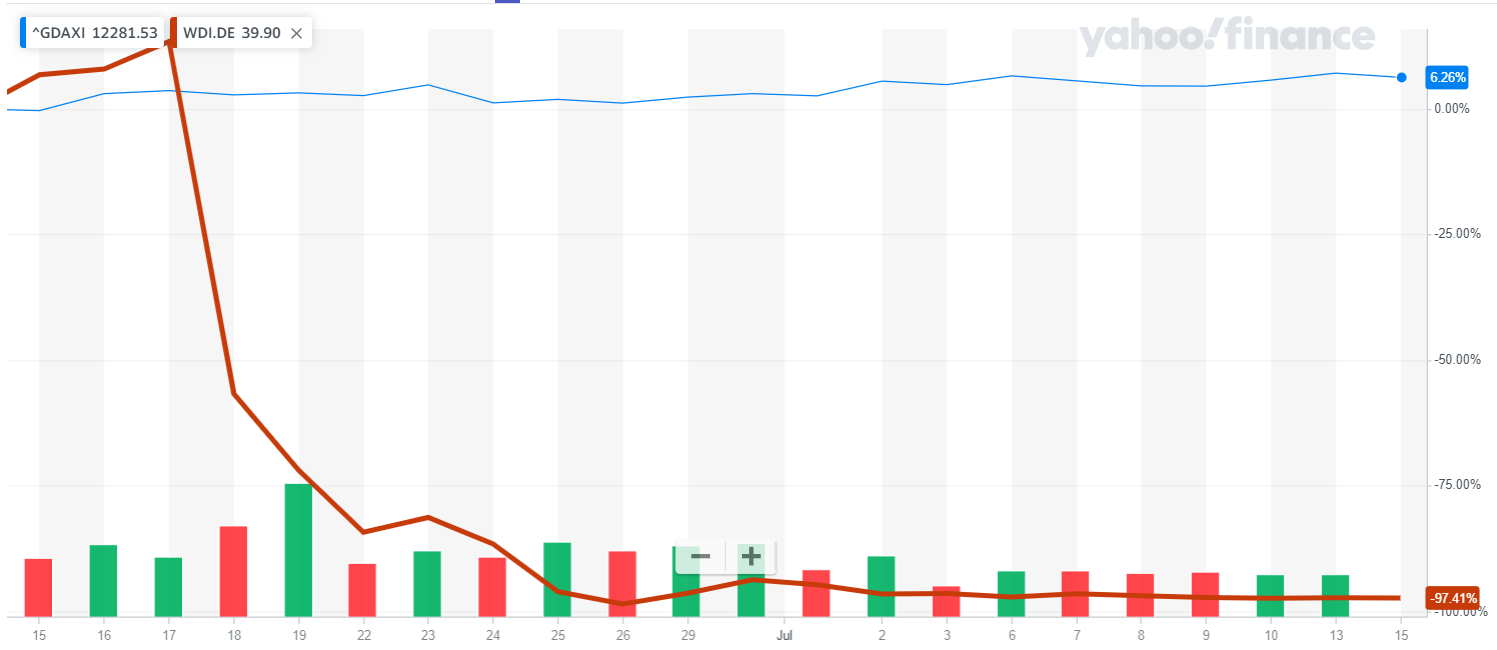

The depth and breadth of this story is more than we can fit into this article. There will be books written on this one, but how did it end up? The chart shows the DAX 30 and Wirecard’s shareprice in percentage terms over the June/July period.

Wirecard down 97%. DAX 30 up 6.26%. A win for the more diversified investors. Wirecard was removed from the DAX 30 this week. The parts of the business that aren’t fraudulent are being picked off by other companies.

The culprits? Chief Executive Officer Markus Braun was arrested, while Chief Operating Officer Jan Marsalek fled the country. Marsalek has been sighted in Belarus, Russia and the Phillipines.

Lessons?

Regulators aren’t always there to protect investors. They’re full of people, and people are prone to whims, biases and beliefs. The German regulator took exception to claims Wirecard was up to no good. After all, if Wirecard was up to no good, that no good behaviour was occurring under its very nose! They were more interested in protecting the company, than protecting investors.

Investors, we haven’t mentioned them yet, but it’s a common tale. And for shareholders it was heroes and villains. Wirecard shareholders believed they were on the side of good because it was the tale CEO Markus Braun spun. He’d point to EY giving the accounts a clean bill of health and the tick from the German financial regulator. How could they be wrong against the evil journalists and short sellers? Investors love a story because as humans we learn and most easily process things by way of storytelling. When you’ve positioned yourself as a believer in a particular story, and put your money at stake, it’s hard to right that ship.

Short sellers. One of the notable parts of this saga is that of the short sellers. One was Australian, John Hempton. Hempton is a smart guy and runs hedge fund Bronte Capital. He had identified Wirecard as a sketchy enterprise a decade ago. Unfortunately, it didn’t do much good. As he notes in Bronte’s June newsletter, while they made some money on the final collapse, overall, they still lost a lot of money over the years waiting for the company to implode. Wirecard went from 8 Euro a share to basically nothing, unfortunately it went there via 191 Euro a share! Meaning if you want to be a short seller, you need to be extremely patient, with a large financial reserve.

This represents general information only. Before making any financial or investment decisions, we recommend you consult a financial planner to take into account your personal investment objectives, financial situation and individual needs.